The Ambidextrous Organization: How to Manage Today’s Business While Building Tomorrow’s

Over the past several decades, the average tenure of companies in the S&P 500 has fallen sharply, with many analyses placing it in the 15–20 year range today.

Here’s the puzzling part:

The companies that fail aren’t small startups with no resources. They’re giants with deep pockets, brilliant employees, and powerful brands.

So why do successful firms fail when their environment shifts? The answer lies in what researchers call the “Success Syndrome.”

The same structures, cultures, and processes that engineer success in a stable market become the architects of failure when things change.

Your efficiency systems become rigid. Your proven processes become sacred. Your winning formula becomes a prison.

The solution is the ambidextrous organization. This framework allows companies to simultaneously manage two contradictory goals:

Exploiting today’s business (efficiency, control, incremental improvement) while exploring tomorrow’s opportunities (experimentation, discovery, radical innovation).

Most companies can’t do both. They focus on one and fail at the other. But the companies that master both create sustained competitive advantage.

The Core Challenge: Exploration vs. Exploitation

Every organization faces a fundamental tension. You need to refine what works today while searching for what works tomorrow.

These two activities directly conflict with each other. A dollar spent on R&D for a speculative technology can’t also be spent marketing your cash-cow product.

What Exploitation Looks Like

Exploitation means refining existing capabilities. You’re focused on execution, efficiency, and predictable returns.

Your targets are current customers and existing markets. You’re optimizing what you already know works.

The metrics are clear:

- Profit margins

- Productivity gains

- Cost reductions

- Operational speed

You can measure success this quarter.

Companies naturally drift toward exploitation. The feedback loops are immediate and the rewards are visible. When you streamline a supply chain, you see the impact in next quarter’s results.

But this creates a trap. You become increasingly specialized in your current domain. You drive out the variability required for future adaptation.

What Exploration Looks Like

Exploration involves search, variation, and risk-taking. You’re experimenting with new technologies and entering unfamiliar markets.

The focus shifts to emerging opportunities. You’re targeting non-consumers and developing capabilities you don’t currently have.

The metrics change completely. You measure:

- Milestones

- Learning rates

- Future growth potential

The ROI is often negative in the early years.

Exploration requires a tolerance for failure. You need speed, flexibility, and the freedom to experiment. “Fail fast” replaces “zero defects.”

The returns are distant and uncertain. Most experiments will fail. But the few that succeed can redefine your entire business.

The Fundamental Conflict

Here’s why most companies fail at both: The organizational alignments required for exploitation and exploration are completely opposed.

- A culture that celebrates Six Sigma efficiency (zero defects) is hostile to rapid prototyping and learning from failure.

- A hierarchical structure that enables control kills the autonomy needed for innovation.

Resources are finite. Management attention is finite. Without deliberate intervention, the exploitation side always wins.

Here are key differences between exploitation and exploration:

| Attribute | Exploitation (Today’s Business) | Exploration (Tomorrow’s Business) |

|---|---|---|

| Strategic Focus | Cost, profit, efficiency, customer retention | Innovation, growth, new markets, adaptability |

| Key Metrics | Margins, productivity, reliability | Milestones, learning, future potential |

| Culture | Disciplined, risk-averse, quality-focused | Risk-taking, experimental, “fail fast” |

| Structure | Formal, hierarchical, defined roles | Adaptive, flat, flexible roles |

| Time Horizon | Quarterly results, immediate returns | Long-term growth, uncertain timeline |

| Leadership Style | Command-and-control, authoritative | Visionary, empowering, collaborative |

The Ambidextrous Solution: Structure Matters

Most organizational designs fail at innovation. They either strangle new ideas with bureaucracy or cut them off from resources.

The answer isn’t choosing between efficiency and innovation. It’s designing a structure that enables both simultaneously.

The Four Organizational Designs for Innovation

Companies typically try one of four approaches.

In practice, three common organizational approaches often struggle with breakthrough innovation, either because the core business overwhelms the effort or because the new work becomes isolated.

1. Functional Integration

You assign innovation to existing departments. R&D handles the research, Marketing handles the positioning, Manufacturing builds it.

This works for incremental improvements. But radical ideas die in the white space between functions. Each department protects its turf and rejects anything that doesn’t fit its existing processes.

2. Cross-Functional Teams

You create project teams with members from different departments. They collaborate while staying within their functional reporting lines.

The problem is divided loyalty. Team members prioritize their “real” job over the innovation project. When quarterly reviews come, the core business always wins.

3. Complete Spin-Outs

You create a legally separate entity to pursue the innovation. Total independence, complete freedom from legacy culture.

But you lose all synergy.

With full spin-outs, there is a real risk of losing integration and leverage, unless access to the parent’s brand, capital, and distribution is deliberately structured.

The parent can’t learn from the spin-out. It’s just another venture capital bet.

4. The Ambidextrous Design

You create structurally independent units with different alignments for exploration and exploitation. But you integrate them tightly at the senior leadership level.

This is one of the most consistently effective organizational designs for breakthrough innovation, as it protects exploratory work from the core business while maintaining senior-level integration.

But it can still access the parent’s assets.

The Integration Engine: Leadership’s Critical Role

Structural separation solves one problem. But it creates another. How do you prevent the organization from fracturing into two hostile camps?

The answer is the senior leadership team. They become the integration layer that holds everything together.

What Ambidextrous Leaders Actually Do

The senior team has four critical responsibilities. First, they formulate a common vision that encompasses both the core and the exploratory units.

This vision acts as glue.

At Ciba Vision, the slogan “Healthy Eyes for Life” gave meaning to both units. The profitable core wasn’t just generating cash. It was funding the future of vision care.

Second, they protect the exploratory unit from corporate antibodies. The core business will always try to kill the new venture to save costs.

Senior leaders must actively shield it.

Third, they manage resource allocation. This is politically contentious. You’re taking cash and talent from a profitable mature business and giving it to a money-losing experiment.

Fourth, they manage cognitive dissonance. Leaders must switch contexts constantly. Discussing operational efficiency in the morning (core) and speculative strategy in the afternoon (exploration).

Research shows that senior teams with higher social integration handle this better. Trust and communication are essential. Without them, the team fragments into factions.

The LEASH Leadership Model in Action

Under Satya Nadella, Microsoft popularized a “learn-it-all” culture over a “know-it-all” one.

Around the same period, Microsoft moved away from the controversial stack-ranking system, which had reinforced internal competition.

Listen: Nadella spent time with engineers and customers to understand the shift to cloud computing. He engaged deeply with both the market reality and the internal culture.

Empathize: He recognized employee frustrations with the bureaucratic “stack ranking” system. He connected with the needs of people in both the core Windows business and the emerging Azure team.

Align: He changed the mission from “A PC on every desk” (product-focused) to “Empower every person and organization” (platform-focused). This vision encompassed both old and new businesses.

Support: He invested heavily in Azure even when it competed with the lucrative Windows Server business. He provided resources and air cover for the exploration units.

Hunger: He instituted the “Growth Mindset” as a cultural pillar. This encouraged risk-taking and learning from failure across the entire organization.

The result?

Microsoft maintained its core profitability while becoming a cloud computing leader. Nadella managed today’s business while building tomorrow’s.

The Hidden Power of Incentive Systems

Here’s a common failure mode.

You incentivize the leader of an exploratory unit based on quarterly profit. That unit will never take the necessary risks.

Exploitative managers should be rewarded for operational efficiency and margin improvement. Exploratory managers should be rewarded for milestones reached and market validation.

But here’s the critical part:

The senior team must be incentivized on aggregate firm performance. If the Head of the Core Business is paid only on their unit’s profit, they’ll rationally refuse to share resources.

When you tie compensation to the success of the entire organization, collaboration becomes rational. Self-interest aligns with organizational interest.

Real-World Evidence: Success and Failure Stories

The theory is proven by real companies. Some mastered ambidexterity and thrived. Others failed and disappeared.

Success: Ciba Vision’s Reinvention

In the early 1990s, Ciba Vision was a profitable but stagnant contact lens manufacturer. They trailed market leaders Johnson & Johnson and Bausch & Lomb.

President Glenn Bradley recognized that the core business of conventional lenses was entering decline. Future growth required radical innovations like daily disposables and extended-wear lenses.

Bradley implemented a classic ambidextrous design.

He cancelled incremental projects in the core to free up resources. Then he established autonomous units for breakthrough projects.

These units were physically separated from headquarters. They had their own P&Ls and hired their own staff with different competencies.

The “Healthy Eyes for Life” vision prevented civil war. Employees in the core business weren’t just “the cash machine.” They were funding the future of vision care.

The result?

Sales tripled from $300 million to over $1 billion in ten years. They successfully launched new products, pioneered low-cost manufacturing, and even spun out a billion-dollar drug business.

Failure: Kodak’s Exploration Without Persistence

Here’s a common myth: Kodak failed because they didn’t know about digital photography.

The truth? A Kodak engineer invented the digital camera in 1975. Management was fully aware of the technology.

The failure was organizational. Kodak would start digital initiatives but repeatedly pull them back into the core when they failed to match film profitability.

Their culture was dominated by chemical engineers and a “razor and blade” business model. Digital photography offered lower margins and required electrical engineering skills.

Contrast this with Fujifilm.

They also faced the death of film. But they demonstrated “exploration persistency.” They used their chemical expertise to pivot into cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Fujifilm’s collagen and oxidation control knowledge transferred to anti-aging skincare. They committed to the exploration through the “valley of death” when it was losing money.

Kodak kept retreating. Fujifilm persisted. That’s the difference between bankruptcy and survival.

Making It Work: Practical Implementation Steps

Building an ambidextrous organization requires deliberate design. Here’s a framework based on what actually works:

Step 1: Diagnose Your Innovation Type

Not all innovations require structural ambidexterity. Start by assessing what you’re trying to achieve.

Is this incremental or discontinuous? If it uses existing competencies and serves current customers, you can use functional or cross-functional teams.

If it requires new competencies and targets new customers, you need structural separation. Breakthrough innovation dies in the core business.

Step 2: Create Structural Separation

Give the exploratory unit real independence. This means physical separation if possible, but definitely organizational separation.

The unit needs its own P&L. It needs to hire its own people with different skills. It needs freedom to set its own culture and processes.

Define clear boundaries. Specify what the unit can decide independently (hiring, metrics, day-to-day operations) and where it must align with corporate standards (legal, brand integrity, ethics).

Select the right leader. You need someone comfortable with ambiguity and risk. Often this is an outsider or a “maverick” insider who’s been frustrated by corporate bureaucracy.

Step 3: Build the Integration Mechanisms

The senior team must meet frequently to manage the interface. Weekly or biweekly meetings are common during the early stages.

Create shared incentive structures. Tie executive compensation to the aggregate performance of the firm, not just individual units.

Identify specific leverage points. What assets from the core can the exploratory unit access? Manufacturing capacity? Sales channels? Customer data?

Create service-level agreements for these assets. The exploratory unit should be treated as a valued customer, not a nuisance asking for favors.

Step 4: Commit to the Long Game

Expect the “valley of death.” The exploratory unit will lose money for years. The core business will complain loudly.

Provide air cover. The senior leader must protect the unit from pressure to show quarterly profits. This is where most companies fail.

Measure with appropriate metrics. Don’t judge the exploratory unit by core business standards. Use milestones, market validation, and learning velocity.

Persistency separates success from failure. Kodak started and stopped. Fujifilm persisted. That’s the lesson.

The Only Sustainable Path Forward

Companies that focus only on exploitation become obsolete when technology shifts.

Companies that focus only on exploration burn cash before finding traction. The difference between renewal and failure is conscious organizational design.

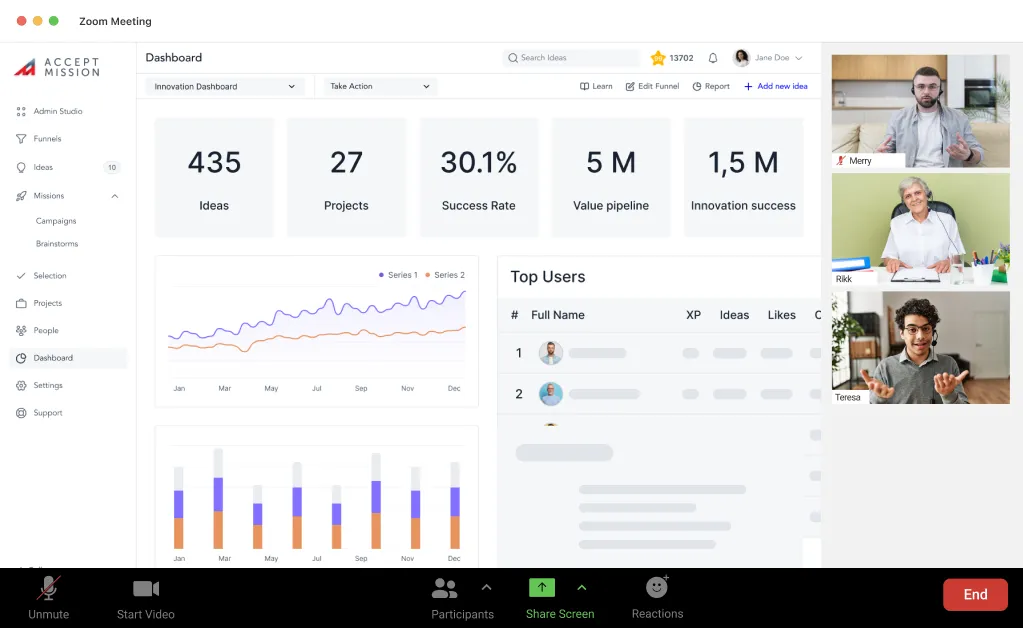

Accept Mission provides the infrastructure to manage both exploitation and exploration in one integrated system. Here’s how Accept Mission helps you build and maintain organizational ambidexterity:

- Separate innovation funnels – Create distinct workflows for incremental improvements (exploitation) and radical innovations (exploration), each with appropriate stage gates and metrics

- Custom scoring criteria – Define different evaluation criteria for each funnel so core business ideas aren’t judged by breakthrough standards and vice versa

- Strategic campaign builder – Launch targeted missions for specific innovation streams, whether collecting efficiency improvements from operations or blue-sky thinking from R&D

- Portfolio visibility – Track both exploitation and exploration projects side by side with real-time dashboards that show aggregate performance

- AI-powered insights – Use AI tools to categorize ideas automatically into the right innovation stream based on risk profile, resource requirements, and strategic fit

- Flexible project management – Convert selected ideas into projects with tracking that respects the different timelines and success metrics of each innovation type

The platform doesn’t force you to choose between efficiency and innovation.

It helps you manage both simultaneously with the structural separation and senior-level integration that research proves works.

Book a demo with Accept Mission today to see how leading organizations are using the platform to balance today’s business with tomorrow’s opportunities.

Our team will show you how to configure custom funnels, scoring models, and workflows that match your specific ambidexterity challenge.