The Psychology of a “Good Idea”: Why Some Innovations Capture Our Imagination

The Segway was supposed to revolutionize transportation. Steve Jobs called it “as big a deal as the PC.” But it flopped.

The Pet Rock was literally a rock in a box. But unlike the Segway, it made Gary Dahl a millionaire in six months.

The truth is that engineering brilliance doesn’t guarantee success. The Segway was a technological marvel. The Pet Rock understood human psychology.

A good idea isn’t just functional. It’s a cognitive event. It navigates the contradictory wiring in our brains: the drive for safety fighting against the pull toward the new.

You can build something objectively better and still watch it fail. Knowing the psychology of ideas helps you design for adoption, not just functionality.

Your Brain on “New” (The Curiosity-Fear Tightrope)

Your brain runs on two competing programs. One screams “Explore!” The other whispers “Careful.”

The Evolutionary War Inside Your Head

Scientists call these forces neophilia and neophobia.

Neophilia is your dopamine-driven urge to explore, the biological reward your ancestors got when they found new food sources.

Neophobia is the protective counterweight that kept them from eating poisonous berries or walking into predator territory.

This creates a boredom-anxiety spectrum:

- Too familiar: Brain tunes it out, filters it into background noise

- Too novel: Amygdala triggers, brain labels it “risky”

- Just right: Novel enough for curiosity, familiar enough to avoid fear (optimal incongruity)

The iPhone in 2007 lived in this sweet spot.

While its multi-touch interface was entirely new (Apple had actually prototyped and rejected an iPod-style wheel version), Jobs anchored it by introducing it as ‘an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator.’

The familiar iPod music experience was the bridge that made the revolutionary touch interface feel acceptable.

Revolutionary ideas that ignore this axis get rejected. Boring ideas that ignore it get forgotten.

The “Aha!” Moment and Why It Matters

When you experience an “Aha!” moment, there’s a measurable neural event happening.

About 300 milliseconds before you consciously realize a solution, there’s a burst of gamma activity in your brain’s right hemisphere.

This is called “neural binding” when separate pieces of information click together into a coherent whole.

Your brain rewards this moment with dopamine.

A good idea lets people experience this micro-insight for themselves. When your product is communicated well, the audience “solves” the puzzle of its utility on their own.

They get their own “Aha!” moment and the neurochemical reward that comes with it.

This is why simple, clear communication matters. It allows the brain to make the connection independently, which feels satisfying.

Innovation lives in the tension between “Ooh, interesting!” and “Wait, what?”

Get that balance right, and people pay attention. Get it wrong, and they walk away. Or worse, they mock you on late-night TV.

The MAYA (Most Advanced Yet Acceptable) Principle

Industrial designer Raymond Loewy created the Shell logo and Air Force One’s livery, and later designed Coca-Cola’s first aluminum can and vending machines.

He had a simple rule: People aren’t ready for solutions that depart too far from what they know. He called this MAYA: Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.

Here’s how the best innovations use MAYA:

- Horseless carriages: Early cars looked like carriages with the same seats and aesthetic, so people could bridge from familiar transport to terrifying new technology

- iPod to iPhone: Apple built trust with the iPod’s simplicity, then introduced the iPhone as a familiar music device that also made calls, before gradually revealing its revolutionary capabilities”

- E-scooters vs. Segway: E-scooters succeeded because they looked like a child’s scooter (familiar). The Segway looked alien (no anchor point)

- Skeuomorphism: Digital objects that mimic real-world counterparts like the Notes app as yellow legal paper and Calendar as leather planner

- Fake camera clicks: The smartphone shutter sound is artificial, but it provides familiar feedback

The pattern is clear.

To sell something surprising, make it familiar. To sell something familiar, make it surprising. The software behaves like the physical world, which satisfies the brain’s intuitive understanding of physics.

If you can’t answer “What’s the familiar metaphor I can anchor this to?” then you’re building something too advanced for the market to accept.

Cognitive Fluency: Why Easy Feels True

Your brain is lazy in an efficient way. It conserves energy using mental shortcuts called heuristics, and one of the most powerful is processing fluency.

Three Types of Fluency That Drive Adoption

When something is easy to understand, your brain misattributes this ease as a signal of truth.

Psychologists call this the illusory truth effect. A confusing “good idea” will lose to a clear “mediocre idea” every single time.

Fluency shows up in multiple ways:

- Perceptual fluency: Simple names, high-contrast colors, and easy-to-read fonts all process faster

- Conceptual fluency: Familiar concepts and mental models feel easier to grasp

- Aesthetic appeal: Beautiful design feels more usable (even when functionality is identical)

- Linguistic patterns: Rhymes feel truer (“Woes unite foes” vs “Woes unite enemies”)”

These aren’t rational assessments. They’re the brain taking shortcuts. Marketers exploit this relentlessly.

“If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit” became famous during the O.J. Simpson trial because the rhyme made it memorable and feel more valid than it deserved.

Your innovation needs to pass the fluency test at every level: name, design, and communication. Otherwise the brain tags it as risky or untrue.

The Fluency Killer: When Understanding Breaks Down

When fluency breaks down, so does adoption.

The curse of knowledge means once you understand your idea, you can’t imagine not understanding it. This leads to abstract communication that breaks fluency.

Here’s what happens when fluency fails:

- Apple Newton (1993): Flawed handwriting recognition created frustration, trust collapsed

- Quibi (2020): High friction (active selection) vs TikTok’s effortless algorithmic feed

- Technical jargon: Assumes prior knowledge, makes audience check out

The practical test is simple. Can a 12-year-old explain your innovation to their friend in one sentence?

If not, it’s too complex. You haven’t done the hard work of making it fluent. And if it’s not fluent, people won’t perceive it as valuable, even if it objectively is.

The Social Psychology of Spread

People don’t just adopt innovations. They spread them. Understanding transmission is just as important as understanding adoption.

Social Currency: Making Sharers Look Good

We share things that make us look good.

Sharing an innovation is identity signaling. It says “I’m smart enough to discover this” or “I have access to things you don’t.” Being the carrier of a good idea confers status.

Social currency shows up in different ways:

- Hidden access: Speakeasy Please Don’t Tell has an entrance inside a phone booth in a hot dog shop (sharing the secret makes you an insider)

- Early discovery: Being first to share a new tool or trend signals you’re ahead of the curve

- Identity alignment: Products that reflect personal values become badges of identity

The question for innovation: Does using your product make someone look smart, cool, or kind?

If the answer is no, people won’t share it. If the answer is yes, they become your marketing team.

This is why status-conscious products spread faster than functional-but-boring ones. The social reward is part of the value proposition.

Triggers and Visibility: Built to Show, Built to Grow

The phrase is “top of mind, tip of tongue.”

Ideas triggered by frequent environmental cues get talked about more. If people can’t see your innovation being used, they can’t be influenced by it.

Here’s how visibility drives adoption:

- White iPod headphones: Apple made them white (not black like competitors) so iPod usage was visible in public. Every user became a walking billboard.

- Environmental triggers: Rebecca Black’s “Friday” song spikes in views every Friday (the day is the trigger)

- Shareability: Quibi blocked screenshots and sharing, killing virality completely. Content trapped in a walled garden can’t spread.

Visibility creates social proof. When people see others using something, it reduces perceived risk and signals “this is normal now.”

The best innovations make usage inherently public, not hidden behind closed doors or private screens.

If your innovation is invisible in use, you’re relying solely on word-of-mouth without the visual reinforcement that drives mass adoption.

The Innovation Adoption Curve: Crossing the Chasm

Take note though that innovation doesn’t spread evenly across society.

It follows a predictable pattern, and most innovations die trying to cross from early enthusiasts to mainstream pragmatists.

Here’s how the curve breaks down:

| Segment | % of Population | Psychology | What They Want |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovators | 2.5% | Venturesome risk-takers | Technology for its own sake |

| Early Adopters | 13.5% | Visionaries seeking advantage | Competitive edge, status |

| Early Majority | 34% | Pragmatic and deliberate | Proven reliability, references |

| Late Majority | 34% | Skeptical of change | Economic necessity, peer pressure |

| Laggards | 16% | Tradition-oriented | Only adopt when forced |

The critical moment is crossing from Early Adopters to Early Majority. Geoffrey Moore called this “the chasm.”

Early Adopters want revolution and tolerate bugs. Early Majority want evolution and need overwhelming social proof.

Marketing that attracts visionaries (“beta,” “disruptive”) actively repels pragmatists who fear risk.

Here’s the thing: The magic happens around 15-25% adoption when social proof takes over. “Everyone else is doing it, so it must be safe.”

If you can’t translate from “cool tech” to “industry standard,” your innovation dies in the valley between vision and pragmatism.

Why Good Ideas Get Rejected: The Psychology of “No”

The brain isn’t wired to embrace change. It’s wired to protect what you already have.

Status quo bias makes doing nothing feel safer than trying something new, even when the new thing is demonstrably better.

This builds on Kahneman and Tversky’s research on loss aversion: the pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

This creates the 3x-10x rule for innovation. Your idea must be dramatically better to overcome resistance:

- Segway: Solved a problem (walking) people didn’t see as painful. $5,000 cost + social risk (looking lazy) outweighed efficiency gains.

- Google Glass: Privacy fears (covert recording) triggered defensive neophobia. “Glassholes” became the label. Social norm violations couldn’t be overcome.

- QWERTY paradox: The Dvorak keyboard promises speed and ergonomic benefits, but almost nobody switches. Even if the benefits were proven, learning it means losing years of muscle memory. The switching cost is too high.

Your innovation doesn’t compete against nothing.

It competes against the comfort of “the way we’ve always done it.” Users overvalue what they already possess: their skills, habits, and familiar processes.

This is why incremental innovation often wins over revolutionary innovation. Small improvements don’t trigger loss aversion or ask people to give up anything significant.

If you can’t offer something 10x better in speed, cost, convenience, or status, you’re asking people to make a change that feels riskier than it’s worth.

Engineering Perception, Not Just Products

The “goodness” of an idea lives in the mind of the person encountering it, not in the product. The iPhone wasn’t just better engineering. It was better psychology.

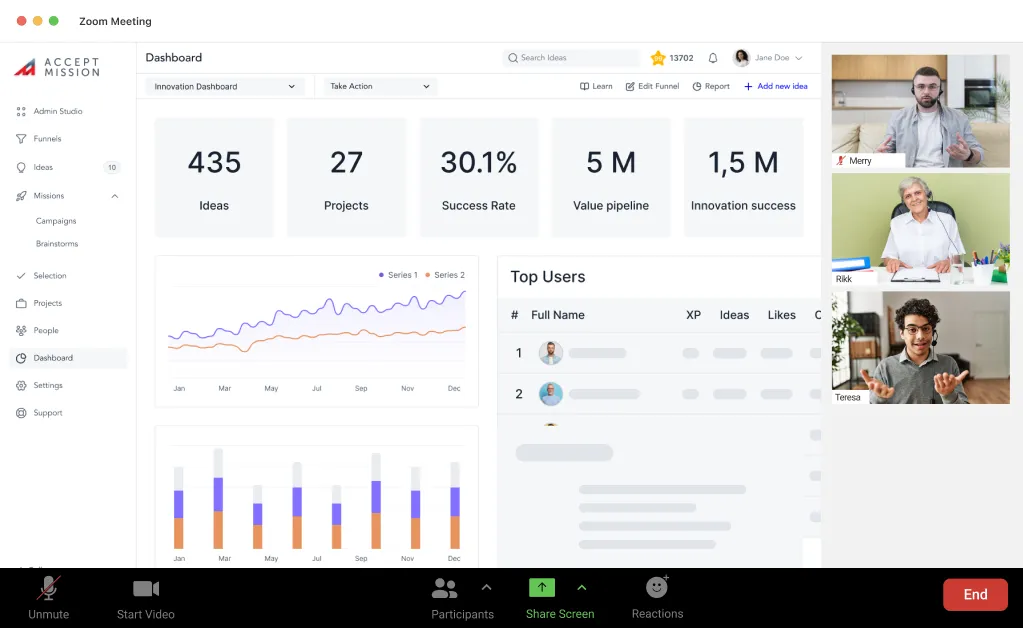

Accept Mission helps innovation teams apply these psychological principles systematically, designing around how people actually think and adopt new ideas.

Here’s how we help you engineer ideas that resonate:

- MAYA-driven presentation: Frame your innovations with familiar anchors and clear visual metaphors that reduce cognitive load

- Fluency optimization: Simple, intuitive interfaces that make complex innovation portfolios easy to understand and navigate

- Social proof built-in: Visibility features that show which ideas are gaining traction, creating momentum through peer influence

- Adoption tracking: Monitor how ideas move through your organization’s adoption curve from innovators to early majority

- Resistance diagnosis: Identify where psychological barriers exist and what level of improvement (3x? 10x?) is needed to overcome status quo bias

Innovation teams spend years perfecting technology.

Accept Mission helps you perfect the psychology: how ideas will be perceived, what mental models users will apply, and what familiar anchor points you can provide.

Psychological resonance creates lasting competitive advantage that’s harder to replicate than any feature.

Ready to build innovations that capture imaginations, not just check technical boxes?

Book a demo with Accept Mission today and discover how to design for the brain you have, not the rational brain you wish people had.