Disruptive Innovation: A Look Back at Christensen’s Theory and Its Relevance Today

Here’s a question that keeps business leaders up at night. Why do well-managed companies fail even when they do everything right?

Clayton Christensen asked this same question in the mid-1990s.

His research into the disk drive industry revealed something shocking. Companies weren’t failing because of bad decisions or lazy management.

They were failing because they listened too closely to their best customers. They invested heavily in what those customers wanted. And that created a blind spot that killed them.

Fast forward to 2025, and Christensen’s theory matters more than ever. Chinese EV makers like BYD are eating market share while Western automakers retreat.

Generative AI threatens to upend consulting and professional services. Healthcare costs spiral while better alternatives sit on the margins.

The pattern is always the same. Market leaders collapse not despite their success, but because of it.

What Disruption Actually Means

Most people use “disruption” wrong. They think it means any big change or hot new startup. It doesn’t.

Disruption is a specific process. It follows a predictable trajectory that Christensen mapped with precision.

Sustaining vs. Disruptive Innovation

The theory starts with a crucial distinction. There are two types of innovation, and they follow completely different rules.

Sustaining innovations make existing products better for current customers.

Think of the iPhone 15 versus the iPhone 14. Or a faster processor in your laptop.

These improvements move along dimensions that mainstream customers already value like speed, power, and resolution.

Incumbents almost always win these battles.

Their processes are built to serve their best customers with better performance. They have the resources and motivation to fight hard.

Disruptive innovations look weak at first.

They underperform on traditional metrics. A 5.25-inch disk drive had less storage than a 14-inch drive. Mini-mill steel was lower quality than blast furnace steel.

But they offer something different.

They’re cheaper, simpler, or more convenient. They appeal to customers who are overserved by current offerings or to people who couldn’t access the product before.

Here’s how they compare:

| Dimension | Sustaining Innovation | Disruptive Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary target | Existing high-end customers | Overserved customers or non-consumers |

| Initial performance | Superior or equivalent | Inferior on traditional metrics |

| Price point | Premium or comparable | Significantly lower |

| Incumbent motivation | High (defend margins) | Low (unattractive segment) |

| Outcome | Incumbents usually win | Incumbents usually lose |

The difference isn’t about technology. It’s about market trajectory and business model fit.

The Two Pathways of Disruption

Disruption enters markets through two doors. Knowing which door matters for predicting what happens next.

Low-end disruption targets customers who are overserved.

They use the product but don’t need all its features. They won’t pay more for improvements they don’t value. A disruptor enters with a “good enough” product at much lower cost.

The incumbent sees eroding margins and willingly exits this segment. They flee upmarket to protect profits. This retreat continues until they run out of places to hide.

New-market disruption targets non-consumers.

These are people who previously lacked the money or skills to use the product. The disruptive product competes against nothing at all.

When your alternative is zero, even inferior performance beats that.

Personal computers disrupted mainframes this way. They were terrible compared to mainframe standards but perfect for individuals who had no computer access.

Both pathways work because incumbents are motivated to ignore them.

The margins look unattractive. The customers seem unimportant. So they focus elsewhere while the disruptor builds strength.

Classic Cases: The Pattern in Action

Theory is nice. Real history is better. These two cases show the disruption pattern with brutal clarity.

Steel Mini-Mills

The steel industry offers the clearest example of low-end disruption. Integrated mills used blast furnaces to make steel from iron ore. They were massive, capital-intensive operations.

Mini-mills used electric arc furnaces to melt scrap steel. They had about 20% lower costs than integrated mills. But the steel quality was poor at first.

Mini-mills started with rebar, which are concrete reinforcing bars. This was the lowest-quality, lowest-margin steel product at around 7% margins.

Integrated mills were happy to exit this market. Why fight over the lowest margins when you could make angle iron and other products with significantly better returns?

So the integrated mills retreated to angle iron. Then mini-mills improved their technology and entered the angle iron market. Integrated mills retreated again, this time to structural beams.

At each step, the pattern repeated.

Mini-mills improved and moved upmarket. Integrated mills fled to protect their margins. Eventually, mini-mills learned to make sheet steel, which is the crown jewel of the industry.

The integrated mills had nowhere left to go. Many collapsed entirely. The survivors did so through acquiring mini-mills and cannibalizing their own business model.

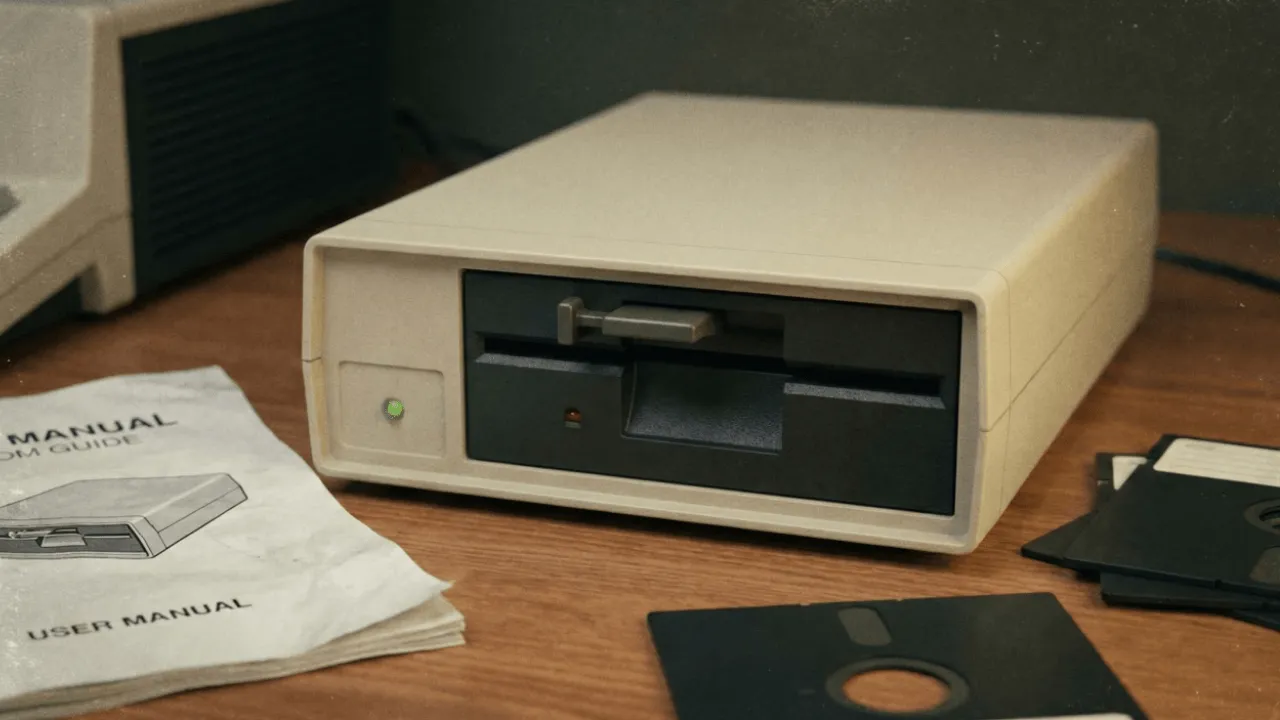

The Disk Drive Industry

Christensen called disk drives the “fruit fly” of innovation. The industry moved so fast you could watch evolution happen in real time.

The pattern played out across multiple generations.

The market moved from 14-inch drives to 8-inch, then 5.25-inch, then 3.5-inch. At each transition, the market leaders were wiped out.

Here’s what happened with 8-inch drives:

They had lower capacity and higher cost-per-megabyte than 14-inch drives. Mainframe customers rejected them outright. The specs were simply inadequate.

But minicomputer makers didn’t need mainframe capacity. For them, 8-inch drives were perfect. They fit the smaller form factor and met their storage needs.

The 14-inch manufacturers held back. They waited for the 8-inch market to become “large enough” to be interesting.

When it finally was, the entrants like Shugart Associates already dominated. They had moved up the performance curve while the incumbents waited.

This pattern repeated with brutal precision.

The 5.25-inch drive disrupted 8-inch drives for desktop PCs. The 3.5-inch drive disrupted 5.25-inch drives for laptops. In each generation, the leaders fell.

The cruel irony?

The incumbents often developed the disruptive technology in their labs. They had the capability. Their best customers just didn’t want it yet.

Disruption in 2024-2025 (Three Critical Battlegrounds)

The theory isn’t just history. It’s unfolding right now across multiple industries. These three sectors show disruption in different stages.

Generative AI: Sustaining Today, Disruptive Tomorrow?

Right now, GenAI strengthens the giants.

Microsoft integrates Copilot into Office 365, making its core product stickier for enterprise customers. Google deploys AI to improve search and workspace tools.

This is classic sustaining innovation.

The technology makes existing products better for high-end customers. Training frontier models costs billions and requires massive compute clusters. Only incumbents can afford it.

But watch what happens at the low end:

Small language models and open-source alternatives are getting better fast. They run on local devices with zero marginal cost. They’re “good enough” for many tasks.

The real disruption targets professional services.

Consulting firms, law practices, and accounting services all operate as “solution shops.” You pay high fees for expert diagnosis and problem-solving.

What if AI can deliver a good enough answer for 1% of the cost?

A small business owner doesn’t need a Big Four accounting firm. They need tax forms done correctly. If an AI agent can do that, it disrupts the entire business model.

The pattern is forming. Expensive experts at the top. Cheap AI alternatives at the bottom. The question is whether those alternatives improve fast enough to move upmarket.

Electric Vehicles: Tesla vs. BYD (A Study in Contrasts)

Tesla revolutionized the auto industry. But it’s not a disruptor in Christensen’s framework. It’s a sustaining innovator.

Tesla entered at the high end.

The Roadster started at $98,950 when it launched in 2008. The Model S started at $57,400 at its 2012 debut (or $49,900 after federal tax credits).

These were premium products with superior performance like faster acceleration and longer range than comparable luxury cars.

Incumbents like Porsche and Mercedes were highly motivated to respond.

They released the Taycan and EQS to compete. This is what happens with sustaining innovation. The fight is fierce because the margins matter.

Well, BYD followed a different path. It started with low-cost electric vehicles targeting China’s domestic mass market that Western automakers largely ignored.

The vehicles were cheap and good enough for urban commuting. But BYD’s advantage goes beyond just low prices.

The company achieved dramatic cost reductions through vertical integration, controlling everything from batteries and motors to semiconductors and final assembly.

This allowed them to undercut competitors by 20-30% while maintaining quality.

Here’s the strategic comparison:

| Factor | Tesla Strategy | BYD Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Entry point | High-end luxury market | Low-end mass market |

| Initial price | $100,000+ premium | $10,000-15,000 economy |

| Performance vs. incumbents | Superior (acceleration, tech) | “Good enough” (range, features) |

| Incumbent response | Aggressive competition | Retreat from segment |

| Disruption classification | Sustaining innovation | Disruptive innovation |

Western automakers are now abandoning small cars entirely.

Ford and GM killed their compact models to focus on high-margin trucks and SUVs. They’re voluntarily ceding the mass market to BYD and other Chinese manufacturers.

It’s the steel mini-mill pattern all over again. The incumbents flee upmarket to protect margins. The disruptors improve and follow them up.

Eventually, there’s nowhere left to retreat.

However, BYD’s competitive advantage stems as much from vertical integration and manufacturing efficiency as from pure low-end disruption.

This makes them a formidable competitor even as they move upmarket.

Healthcare: The Unfinished Revolution

Healthcare should be the biggest disruption story of the decade. The economics are screaming for change. But progress is slow because regulation protects incumbents.

The pattern is clear. Care needs to move from expensive hospitals to lower-cost settings.

Retail clinics at CVS and Walmart can handle routine diagnostics for a fraction of hospital costs. Home health models deliver care in living rooms instead of emergency rooms.

Startups are trying to execute the playbook.

Curai uses AI to augment primary care delivery via chat.

The AI system (which the company reports has ~90% diagnostic accuracy) assists licensed clinicians, enabling one provider to manage far more patients than traditional practice allows.

Patients pay around $29/month for unlimited text-based consultations with human doctors supported by AI.

TytoCare provides FDA-cleared diagnostic devices for home use (including otoscopes, stethoscopes, and thermometers) that collect exam data for remote interpretation by clinicians.

Rather than replacing doctors, the devices extend clinical reach into homes, schools, and underserved settings.

The barrier is regulation.

Licensing laws prevent nurse practitioners from doing tasks they’re capable of performing. AI can’t diagnose even when it’s more accurate than humans.

But these rules protect the incumbent guild of physicians.

Disruption theory predicts that technology eventually overwhelms these barriers. When the cost differential becomes too extreme, society demands change.

Healthcare is approaching that breaking point.

The Six-Question Framework for Practical Implications

So how do you know if you’re facing disruption? Christensen created a diagnostic framework. Six questions that reveal what you’re really dealing with.

Ask these about any innovation or competitor:

- Does it target non-consumers or overserved customers? If it targets your core customers with a better product, that’s sustaining innovation. Expect a fight you might win.

- Is it initially “not as good” as existing solutions? True disruption starts inferior on traditional metrics. If it’s better right away, it’s not disruptive.

- Is it simpler, more convenient, or more affordable? These are the vectors of disruption. Lower cost with adequate performance is the classic pattern.

- Is there technology enabling improvement over time? The disruptor needs a path to move upmarket. Without improvement potential, it stays niche.

- Does it have a low-cost business model? Can it profit at prices you can’t match? If not, you can compete on cost and win.

- Are incumbents motivated to ignore it? This is the key. If the margins look attractive, you’ll fight back. If they look unattractive, you’ll retreat, and that’s when disruption happens.

If you answer yes to most of these questions, disruption is coming. The timeline might be years or decades. But the trajectory is set.

The framework works for offense too.

If you’re trying to disrupt an industry, these questions show whether your strategy fits the pattern. If it doesn’t, you’re picking a sustaining fight with better-resourced competitors.

Navigating the Disruption Dilemma

Success creates the conditions for failure. The very things that make you great like listening to customers and focusing on margins become the chains that hold you down.

Understanding disruption is one thing. Managing your innovation portfolio to respond to it is another.

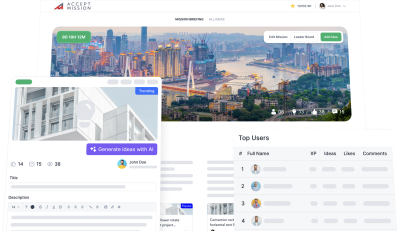

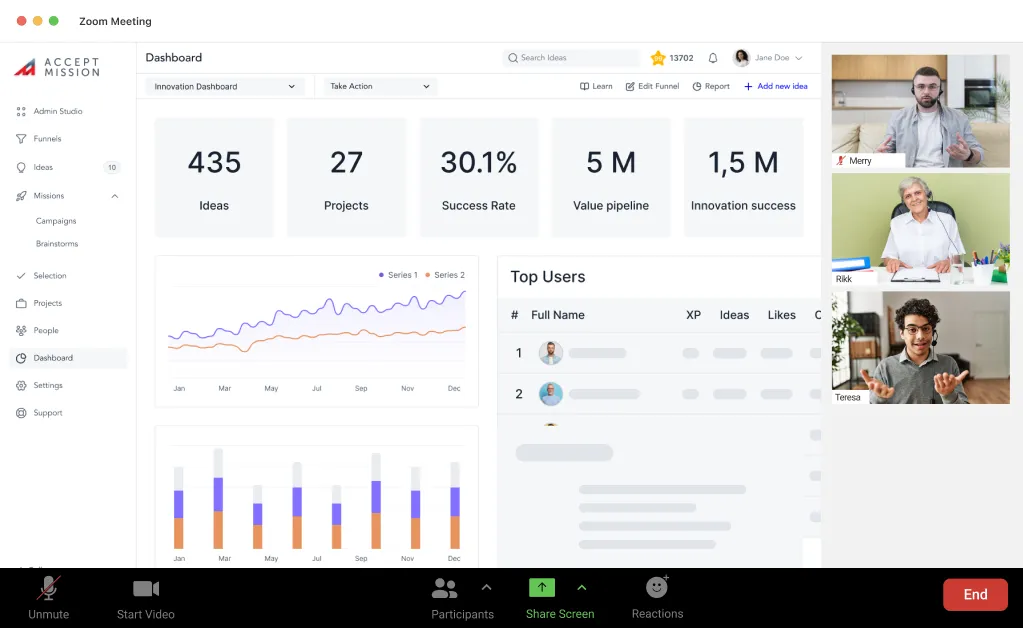

Accept Mission helps you spot low-end threats early, evaluate which ideas deserve resources, and execute fast enough to either disrupt or defend.

The platform structures your innovation process so you can identify potential disruptions and move ideas from concept to execution before competitors do.

Here’s how Accept Mission supports your disruption strategy:

- Launch targeted innovation campaigns to spot low-end opportunities and new-market footholds before they become threats

- Use AI-powered scoring to evaluate which ideas fit the disruptive pattern versus sustaining improvements

- Build innovation funnels with stage-gates that separate exploratory projects from core business optimization

- Track portfolio health with real-time dashboards showing your mix of sustaining versus disruptive initiatives

- Enable cross-functional collaboration so teams can develop disruptive ideas without bureaucratic friction

- Measure ROI and strategic fit to ensure disruptive projects get resources even when margins look unattractive initially

The platform creates visibility into your entire innovation pipeline.

You can see where ideas are stuck, which ones are moving upmarket, and whether you’re investing enough in potential disruptors.

Most importantly, Accept Mission helps you ask the right questions at the right time.

Is this idea targeting overserved customers or non-consumers? Does it have a path to improve over time? Will incumbents ignore it?

The six-question framework becomes actionable when embedded in your innovation process.

Book a demo with Accept Mission today and see how leading organizations are turning Christensen’s insights into competitive advantage.